Access to legal assistance is fundamental to gender equality

Legal support for women and the pros and cons of online hearings take over today’s sessions

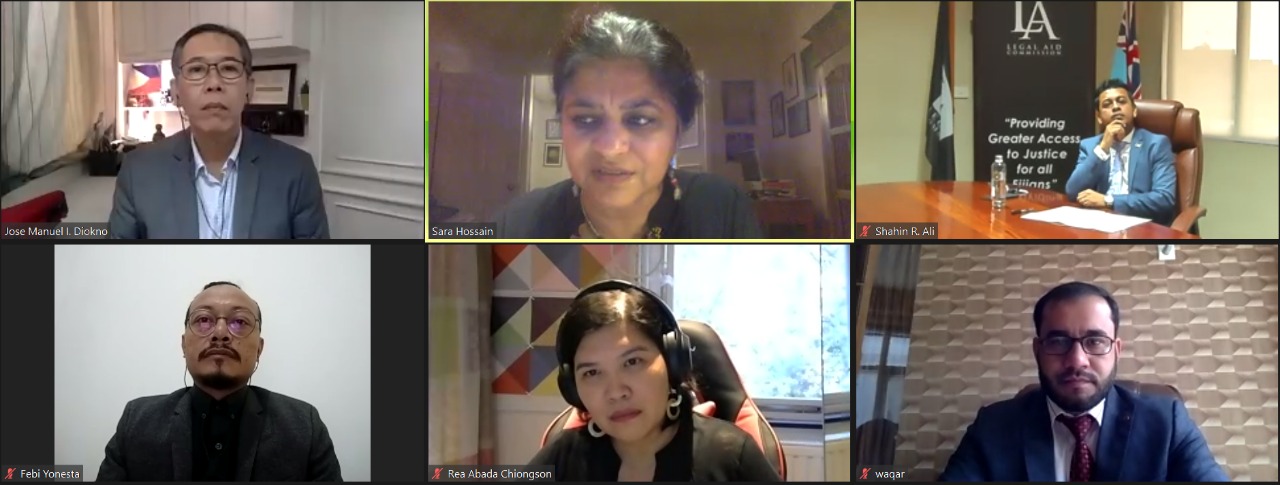

On the third day of the 4th International Conference on Access to Legal Aid in Criminal Justice Systems (ILAC), legal aid for women were at the spotlight. It became clear that the effective integration of gender issues into all areas of activity of law operators effectively contributes to equal justice for all, as set forth by the 2030 Agenda of the United Nations.

Women have specific needs that require extra care when it comes to legal aid. After all, they are more exposed to poverty, abuse and lack of social protection. Studies show that they are also more likely to commit specific crimes, such as crimes against private property, as these are directly related to precarious social and economic conditions. Experts also point out that drugs trafficking and prostitution often constitutes, in many situations, attempts to escape an abusive home life.

In addition, in certain countries, women do not have access to family wealth, which can make it difficult to have adequate legal aid. As a result, understanding and “navigating” the judicial system becomes even harder. Illiteracy and insufficient knowledge of one’s own rights also leads to increased vulnerability.

Freedom or oppression

Opening today’s discussions, Jose Manuel Diokno, Founding Dean, Faculty of Law at the University of La Salle (DLSU) and Chairman of the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG) in the Philippines, categorically stated that the law can be used either to free or to oppress people. “In the Philippines, the legal system generates much injustice, which is somewhat curious. We seek to understand why this is so in order to deal with the issue and alleviate social injustices.”

He also highlights the important work carried out by his organization, which in addition to legal assistance, also encourages “meta legal” action, which consists of mobilizing individuals towards rights preservation. “The poor and oppressed can and must use the law to free themselves”, he concluded.

Domestic violence

In the Fiji Islands, says Shahin R. Ali, Acting Director of the Legal Aid Commission and second panelist of the day, the pandemic has made the government more aware of the need to provide legal aid for the population, especially to marginalized groups, such as women and children.

As it is the case in other parts of the world, social isolation has contributed to the number of cases of domestic violence. Fortunately, however, women are more prone to reporting such incidents and making use of the country’s justice system. All reports are investigated, even if the victim decides to drop charges. Such cases have also been classified as “urgent” during the pandemic.

Moreover, the government has invested in education and guidance for girls and women via social media networks. “We have come a long way in granting women access to legal aid. Empowering the most vulnerable is our responsibility”, argues Ali.

Multidimensional approach

To Rea Abada Chiongson, Senior Legal Advisor on Gender, International Development Law Organization (IDLO), tackling gender discrimination requires a multidimensional approach that brings together gender, law and development so that comprehensive and long-lasting solutions may be achieved. Good laws, when well-implemented, are vital to women’s access to legal aid; however, gender equality and empowerment are also crucial for these laws to be fully enjoyed by women and girls.

In the past, women have faced many injustices, a situation that only got worse with the pandemic: they are more isolated at home, sometimes with limited digital access, exposed to domestic violence and unable to access certain healthcare services. Fortunately, in some countries such as Mongolia, good practices have emerged, including the distribution of hygiene “COVID kits” to those who live in poorer neighborhoods. “It is difficult for women to access legal aid if they do not have basic hygiene care”, notes Chiongson. She also draws attention to the establishment of multidisciplinary groups of law operators dedicated to discuss issues that are relevant to women.

Reintegration

Nearly 30 years of civil war and Taliban rule ended up decimating Afghanistan’s justice system, highlighting the urgency for reforms. In this context, ILF has represented more than 60,000 criminal cases to date, said M. Nabi Waqar, Director of the International Legal Foundation (ILF) - Afghanistan.

The pandemic, says Waqar, has changed every aspect of people’s lives in Afghanistan and the world. But being imprisoned affects the individual even more, as it often interrupts one’s educational progress, could originate or exacerbate psychological issues and alienates families - among other impacts - which is why legal aid is so important.

ILF has worked with female detainees in many ways: by providing them with cell phones to enable legal guidance or helping keep basic hygiene conditions within prisons. More importantly, however, is social reintegration, since they are subject to strong discrimination.

Land grabbing

Febi Yonesta, Head of Organizational Development, Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI), addressed land grabbing, one of the biggest problems in Southeast Asian countries. The practice is defined as a large-scale acquisition/possession of land (usually 200 hectares or more) by private investors or governments aimed at farming and extractivism. Such acquisitions undermine food security in these countries, making many people landless due mostly to the lack of legal property ownership. There are cases of people who have been removed by the State itself or with its approval.

In recent years, as land grabbing has scaled and become more systematic, the number of evictions skyrocketed. Long stretches of land have been confiscated and turned over to foreign or national investors, and laws have been changed to favor private interests. These “investors”, in turn, seldom abide by any codes of conduct, exposing small farmers to the risk of poverty.

Indonesia’s long history of gender discrimination and land litigation is largely due to major infrastructure works. “It is not in the government’s interest to deal adequately with the issue. During the COVID-19 crisis, the problem has worsened and YLBHI has been working to help these people.

Caution in scanning

On second panel of the day, which focused on Africa, Europe and the Middle East, Deputy Minister of Justice of Ukraine, Valeriia Kolomiets, spoke about the changes implemented in the country’s legal aid system in the past year, especially when it comes to logistics. Presently, there are about 500 service units that operate as close as possible to target communities. The pandemic also resulted in greater digitalization and use of mediation techniques in civil cases - in detriment of litigation - as it is a cheaper and more effective.

Despite being a helpful tool in times of Coronavirus, remote hearings require caution, experts agree. Ilze Tralmaka, Legal Aid Policy Officer at Fair Trials reported different problems associated with the tool. In her opinion, these difficulties undermine the defendant’s right of defense, as well as their prerogative to effectively understand the legal procedures.

She also points out that remote hearings impose time limitations and prevent personal access to a lawyer, access to material evidence and imprisonment conditions, especially by vulnerable groups. At the other end, the experience has also proved difficult for lawyers and judges, who need to understand the defendant’s vulnerabilities and address them properly. “Remote hearings are considered a cheap and fast solution for overcrowded systems, but fast and cheap should not be a reference. We must seek a fairer trial, not a faster one. For this reason, the adoption of the tool in a permanent way demands more careful consideration”, says Tralmaka.

Drugs and war

Chinelo Elizabeth Uchendu, Lawyer and National Coordinator of Legal Advocacy and Response to Drugs Initiative (LARDI) in Nigeria, and Nadia Carine Fornel Poutou, President of the Association des Femmes Juristes Centrafricaines, closed the panel dealing with two sensitive issues: the fight against drugs and the impact of violence on vulnerable populations.

Uchendu explained that drug dealers are often seen as wealthy, but their reality is quite different. It is a very vulnerable group, she says. In Nigeria, since the advent of the pandemic, all legal procedures have been suspended. As a consequence, there have been human rights abuses in prison units and police stations, which are overcrowded. COVID-19 also caused drug testing centers to close, leaving many individuals with no prospect of trial. So far, attempts to digitize processes have not been effective, but Uchendu expects improvements in the future.

Nadia Poutou commented on the dire conditions experienced by her country, the Central African Republic, where civil war has had terrible consequences for the population, especially children and women. The legal system has serious operational problems, an issue that has been dealt with by international and local organizations, with a special focus on human rights and the right to justice for women. In this sense, she highlighted the work of the nine legal assistance clinics maintained by her organization with the support of volunteers, who have already made access to legal aid possible for 1,170 people.

Women in Argentina and Brazil

In the third panel of the day, dedicated to the American continent, the Public Defender of the State of Mato Grosso & Coordinator of the Public Defender’s National Commission on Women’s Rights in Brazil, Rosana Leite, discussed Law n. 11.340, also known as the “Maria da Penha” Law. The legislation was the first to recognize homo-affective unions in Brazil; in addition, it deals with domestic violence. “Maria da Penha is the third most important law in the world, allowing civil and criminal cases to be filed together.”

According to the UN, 7 out of 10 women will be subject to violence throughout their lifetime. In Brazil, during the pandemic, while domestic violence statistics became less available, there was an increase in femicide rates. The main reason is when the perpetrator resorts to violence out of jealousy (or anger from an attempt) to separate. The second cause is frustration upon arriving home and not finding the arrangements he wished for.

“Women are killed inside the home; men, outside”, asserts Leite, adding that during the lockdown, domestic violence cases could be reported and protective measures issued online. Women were also given priority in body examinations.

In Argentina, several steps were taken to allow access to legal aid during the pandemic, especially for women. One concern was to maintain protective measures, a request made by the Defender’s Office to the House of Representatives. Notifications and reporting were also a concern during lockdown, and, as a solution, WhatsApp came into play. But the main issue, which was solved in a joint effort with Banco de la Nación, was maintenance payments continuity, claims Raquel Asensio, Coordinator of the Commission on Gender Issues of the Federal Public Defender’s Office in Argentina. “We also changed the way cases could be reported, which can now be done by phone, app and e-mail.”

Youth and immigrants

The Montreal Community Legal Center (CCJM) works with immigrants, a very vulnerable group and traditionally one with hardest access to the Public Defender’s Office. In the pandemic, explains Gilles Trudeau, the organization’s Corporate Secretary, “we were able to convince the authorities to reduce detentions and expand access to legal aid”. In order to ensure access to services, new technologies were used to facilitate communication with clients, including video conferences and a hotline. “We understand that conducting hearings over the phone was not ideal, but it was better than not having hearings at all.”

Closing the day’s panels, Fran Sherman, Professor and Director of the Juvenile Rights Advocacy Program at Boston College Law School, gave an interesting account of the holistic approach to youth care, which was severely hampered during the pandemic, as closure and physical contact is of fundamental importance when dealing with this public.

The model has four pillars: the provision of legal and non-legal services to satisfy all client’s needs; dynamic interdisciplinary communication; well-trained professionals in different areas of expertise, and a strong understanding and connection with community services. A survey carried out in the state of Louisiana revealed that 60% of adolescents were satisfied with the approach. Approval rates tend to increase in line with relationship duration with the team and case complexity.

VOLTAR